Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a disorder that is characterized by high reactivity or sensibility to external or internal stimuli that might remind one of the traumatic event. It involves intrusive memories, recurrent dreams, states of dissociation to the environment and self, and states of high anxiety. So-called ‘flashbacks’ are very common in PTSD, during which the individual returns in memory and body (for example, through muscle contraction) to the event, in a way reliving the trauma experientially.

PTSD can develop after any traumatic event, whether lived or witnessed (for example, some people develop PTSD after witnessing a car accident). There are individuals who are more predisposed to develop PTSD, due to multiple causes, such as genetic predisposition, clinical history of substance abuse or other mental disorders, and lack of resilience, a multidimensional psychological factor that has recently been widely studied in the psychological field. However, anyone can develop PTSD after traumatic experiences.

PTSD can cause the individual to avoid certain situations that can trigger these extreme reactions of dissociation or anxiety, sometimes severely limiting one’s level of self-sufficiency and confidence. It can also impact memory, causing selective amnesia around the trauma. Additionally, many of the symptoms seen in depression are often observed, such as negative thoughts, fatigue, anhedonia and other negative emotional states. It is not uncommon to see behavioral problems, expressed through anger and frustration and self-sabotaging behaviors.

Individual differences, or in other words, personality differences and other factors, cause important contrasts in the reaction and response to trauma by individuals. For example, today we talk about ‘fight, flight, freeze or fawn’ responses to stress. Our sympathetic nervous system is responsible for this response, sometimes appropriate (e.g., to run away from a dangerous animal) but often, especially in individuals with trauma, excessive or inappropriate (e.g., palpitations and sweating in a non-threatening social setting).

Someone with PTSD is also 78.5% more likely than those without PTSD to develop a comorbid disorder, with substance abuse, depression, and anxiety disorders being the most common. This creates a great deal of social, occupational and functional difficulties.

Antidepressants are usually prescribed for the treatment of PTSD, in addition to psychotherapy. There are several modalities that can show good results, such as EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing), CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy), and body therapies such as TRE® (exercises to relieve tension and trauma; which we work with at Clinica Synaptica) or sensorimotor therapy.

However, pharmacotherapy alone does not usually have good results – up to 30% of patients do not respond, and less than 30% go into remission. In addition, many often get worse before they get better, creating a high-risk period of time for the individual. For this reason, new drugs that can facilitate the therapeutic process continue to be investigated. Ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP) is one of them.

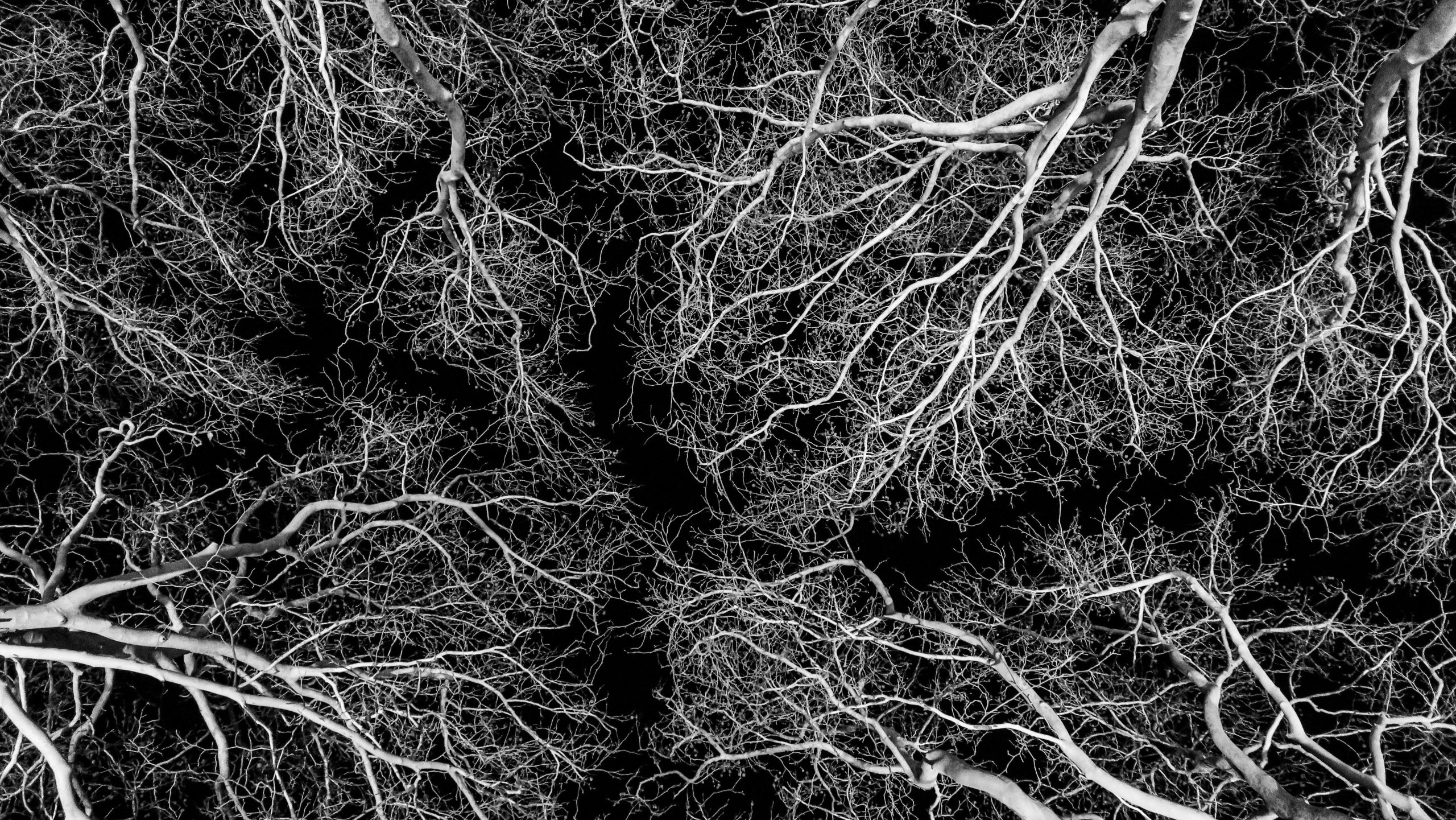

Some researchers postulate that the symptoms of PTSD may be caused or affected by glutamate-mediated loss of neural connections – ketamine in turn enhances the neural connections in these circuits, thus combating the impact of PTSD. This disorder causes hyperactivation of NMDA receptors, of which ketamine is an antagonist. Additionally, ketamine allows the exploration of traumatic memories from a different state of consciousness than usual, creating an opportunity to work through these difficult moments through the therapeutic process.

Evidence

A randomized study with 41 patients with chronic PTSD performed one infusion with ketamine and one with midazolam, two weeks apart. Some patients did the midazolam session before and others the ketamine session, although neither they nor the administrators knew which drug was administered in either session. PTSD symptomatology was measured 24h after infusion, and significantly greater improvement was seen after the ketamine session than after the midazolam session.

Additionally, there are several isolated case descriptions in both adults and children showing good results. However, these studies also show that maintenance of the effects is complicated. For example, a case using a single infusion of ketamine showed a reduction in symptomatology for 15 days, however the patient then returned to the previous state within 24 hours. It is possible that following the protocol used for treatment-resistant depression, performing several sessions over a short period of time, the effects may be more long term, but rigorous scientific research is needed to verify this. Another isolated case described how a patient with bulimia nervosa complicated by several traumatic events received 18 infusions of ketamine-assisted psycotherapy, resulting in a complete and sustained remission over time.

On the other hand, it is important to mention that there is some evidence pointing toward a contraindicated use of ketamine in PTSD for patients who have had recent trauma. One study showed a negative psychoactive impact of esketamine and ketamine in these patients, with esketamine being somewhat more harmful than racemic ketamine. The authors postulate that ketamine may cause overstimulation of glutamate receptors, thus accentuating dissociative symptoms and traumatic memories.

Further research is needed to determine an appropriate protocol for the treatment of PTSD with ketamine-assisted psycotherapy. The evidence already gathered shows great potential for this therapy in this setting, but it is important to always ensure a safe and effective process for patients.